This Is Us, Episode 2: Los Angeles. Kevin, having decided he can no longer stomach being associated with such a lowbrow show, has clamorously quit The Manny, the awful sitcom he’s been starring in. At a party a few days later, his agent, Lanie, in an attempt to save Kevin’s career, arranges a meeting with Mr. Manning, the network president. Manning is in a foul mood because of Kevin’s impetuous departure from the show. He could conceivably sue the actor and bankrupt him.

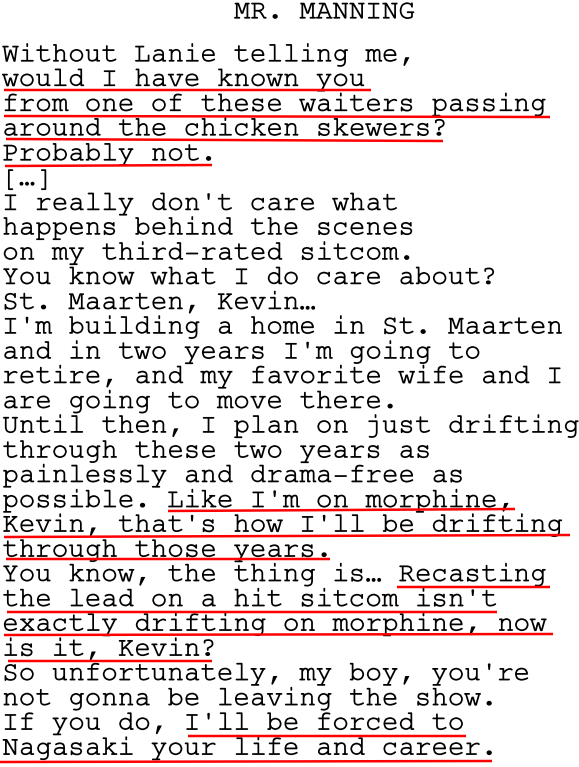

The president’s attitude, which at the beginning of the exchange seems friendly and even paternalistic (“You’re a good kid, Kevin. I appreciate your honesty. The show, it’s a solid performer, but it’s not the biggest thing on my network.”), soon reveals its hostile intention. Here is the core of the man’s speech (with my emphases).

Watching the episode, following (and appreciating) this scene, I was reminded of the importance of sarcasm. A recurrent ingredient in writing dialogue, especially for TV. (Just think how often Aaron Sorkin has recourse to it in his series.) Sarcasm abounds in Billionaires, House of Cards, House M.D., Suits…

So, I tried to sketch a list of sarcasm’s DNA — a checklist of its main aspects:

- Sarcasm is aggressive, even if in different degrees, depending on the case. It is motivated by anger. This is what makes it different from sheer irony.

- It speaks to our desire to show off. It makes us think: I wish I could say the same — have the opportunity to speak my mind out loud the same way this character does.

- It is politically incorrect. Sarcasm leverages ideas generally considered inappropriate to be said out loud (widely-believed, seldom-expressed ideas — that morphine could be pleasurable, that waiters occupy the lowest rung in Hollywood society, etc.).

- It is pragmatic and disenchanted. Sarcasm’s target is hit as if s/he were the straw that broke the camel’s back. The sarcastic one’s anger seems fed by the disturbing evidence that life is too complicated (the life of a network president quite certainly is). This is like a background thought. The misstep of the victim (Kevin quitting the sitcom) is particularly annoying in this already-critical context (the workaholic environment of most TV shows).

- Sarcasm is pessimistic. No big ideals, no hope of taking a step towards a better world (Mr. Manning is not worried about making his mark with a great show before retiring…). The sarcastic character just aims at eliminating one of the many troubles life brings with it.

- It is confidential. A let’s-be-completely-honest approach — a man-to-man approach — is the main frame applied to the situation.

- Sarcasm is often technical. It counts on the knowledge of rules, disciplines, customs, and how-to experiences learned in the field. A set of ideas typical of specific social or professional milieus ( Maarten as an exclusive resort for former Hollywood executives; chicken skewers as usual food in parties; morphine, which is a medicine but also a drug…).

- It is exaggerated. It makes the most of hyperbole (Kevin is more anonymous than the waiters; an absence of troubles is like being on morphine; don’t just destroy someone, but Nagasaki them). Sarcasm is heightened dialogue. So…

- It is lethal. It takes no prisoners. The victim at the end is mortified. But…

- It is also ambiguous. Usually, at the beginning of a sarcastic dialogue, sarcasm is hidden behind benign appearances. It is as if the victim is softly wrapped in the coils of a boa. When the sarcastic intention becomes evident, it’s too late to escape.

- Finally, sarcasm is creative. It uses metaphors and similes (in our scene from This Is Us: waiters, morphine, a nuclear bomb…). At best, it creates new associations. It is smart. That’s why well-written sarcasm is always a pleasure — if not for the heart, then at least for the mind.

Be First to Comment